On beş yıl önce başladığım devasa bir kişisel projeyi bitirdim.

Marx ve Engels okudum.

Daha doğrusu Marx ve Engels'i okudum.

Marx ve Engels'in yazdığı hemen her şeyi okudum. Ve bu ödevi birkaç gün önce bitirdim nihayet. (Bu notu ben İngilizce yazdımdı önce, eğer bu not çeviri kokuyorsa, çeviri olduğu içindir.)

Niye yaptım böyle bir şey?

Üniversitenin ilk yıllarıydı. "Ne yapmalı" diye düşünüyordum. Bunu ciddi bir strateji sorusu gibi değil de, daha çok "hayatımla ne yapacağım şimdi?", "nasıl faydalı olunuyor topluma falan?' ve "dünya nasıl kurtarılır?" sorularının karışımı olarak düşün. Bunlar yirmi yaşında biri için makul herhalde, değil mi?

Sonra bir dünya solcu grupla tanıştım.

Birkaç dünya belki hatta.

Her biri, bu sorulara kendi özgün yanıtları vardı. Ve eşzamanlı bölünme, tartışma, ayrışma, birleşme, kuruluş falan filan süreçlerinde takılıyorlardı.

Bu grupların bazıları anti-marksistti, bazıları marksistti, bazıları öz-marksistti, bazıları hakiki öz marksistti.

Çok karıştı kafam.

Bunların hepsinin aynı anda haklı olması mümkün görünmedi bana.

Keyfim kaçtı bu sonuca vardığımda. Yüzyıllarca tartıştıktan sonra, ana konuların hiçbirinde hiçbir ciddi sonuca varmamışız gibime geldi.

Taktım kafaya; yorumların arkasında takılmayacaktım. Bunun yerine, kendime bir söz verdim: ana kaynakları okuyacak, Marx ve Engels'in ne dediğine dair kendi versiyonumu oluşturacak, ve ancak bundan sonra yorumların arkasına takılacaktım.

Yıl 2011'di. Marksistleri okumayı neredeyse tamamen bıraktım, ve Marx'ı okumaya başladım.

Tam olarak ne yaptım?

Kronolojik sırada Marx ve Engels'in eserlerini okudum.

"Eserler" derken kast ettiğim

- onlar hayattayken kitap olarak yayınlanan her şey (Kapital'in üç cildi, erken dönemlerdeki polemikler (Kutsal Aile falan), geç dönemlerdeki polemikler (Gotha programı şeyleri), güncel politika hakkındaki kitaplar (Brumaire falan), ders kitabı gibi şeyler (Engels'in Anti-Dühring, Feuerbach gibi eserleri);

- Komünist Lig ve Birinci Enternasyonel'in tüm yazışmaları;

- hemen hemen tüm elyazmaları (1844 felsefi ekonomik notları, Grundrisse, 1861-63 ekonomik elyazmaları);

- gazete yazılarının çoğu; ve

- tüm mektupların muhtemelen yarısı.

Yani eğer şu tüm eserler listesine bakarsan, orada (mektuplar hariç) kalın yazılmış her şeyi okudum ve kalın olmayan bazı şeyleri de okudum. (Mektupları derlenmiş bulmak imkansız gibi bir şey, eğer MECW ciltlerine gömecek bir hazinen yoksa.)

Ne öğrendim?

İlk öğrendiğim şey şu: Çoğu marksistin ve hemen hemen bütün anti-marksistlerin, Marx'ın ne dediği hakkında hiçbir fikri yok. Genellikle, kendi görüşlerinden başlıyorlar, sonra bu görüşü Marx'ın yazılarına bulmaya çalışıyorlar.

Biri "Marx şunu dedi." veya "Marx şöyle böyleydi." dediği zaman, çoğunlukla en iyi ihtimalle bir lafı cımbızlıyorlar, veya bir yorumun yorumunun yorumuna referans veriyorlar.

Bundan daha somut olarak, belki birkaç şey paylaşabilirim seninle:

- Yazıların bağlamından habersiziz. Eserlerin yarısı, başka yazarlara bazı spesifik eleştiriler getirdikleri tartışma yazıları. Solcu halkımızın cımbızladığı alıntıların çoğu, genel ifadeler değiller, aksine o dönemdeki bazı somut saçmalıklara verilmiş somut yanıtlar. Yani alıntılanabilir şeyler değiller bunlar. Bu insanlar polemik yazılarıyla binlerce sayfa doldurdular; ve çoğunlukla bu sayfalardaki anlamı sırf kulağa havalı geliyor diye bir tweet'e indirgemek mümkün değil.

- Yine bağlam açısından, terminolojiden habersiziz: Öğrendiğim birçok şeyi unutmam gerekti, çünkü başlangıçta kitapları sanki bugün yazılmışlar gibi okuyordum. Ama "organik" (organa benzer), "objektif/nesnel" (nesneyle alakalı) ve "çelişki" gibi lafların bugünkü anlamının Marx ve Engels'in aklındaki şeyle arasında uçurumlar var.

Bunun üstüne şunu ekle: yazıların yarıdan fazlası, ekonomi politik eleştirisine adandığı için, bir de o çerçeveyi verili alıyorlar. Sürmekte olan bir tartışmanın parçası olduklarından, kendi dönemlerinin terimlerini kullanıyorlar. Mesela "en ileri üretim biçimi" dediklerinde kast ettikleri "ilerleme", dikkatle tanımlanmış bir kavram ve ardında "emek üretkenliği" var; ve burada "üretken" lafından da "bir başkası için artık-değer üretmek" anlamak lazım. Yani demem o ki, bir metnin ne demeye çalıştığını anlayabilmek için, sözcüklerin tam olarak neye karşılık geldiklerini bilmek çok faydalı oluyor.

- Öğrendiğim bir önemli şey, yöntem. İçerik değişiyor, çünkü etkileştikleri bağlam değişiyor. Alman köylüleriyle ilgili bir kitaptan bir cümle alıp bunu Erfurt programı eleştirisiyle kıyaslarsan, çelişkili cümleler bulabilirsin. Çünkü farklı şeylerden bahsediyor bu eserler. Bunlar arasında sürekliliği ve tutarlılığı sağlayan şey, tarihsel materyalist yöntem. Sınıf analizini ve diyalektiği, gerçek dünyadaki durumlara uygulayıp somut sonuçlar çıkarıyorlar.

- Hem Marx hem de Engels, bir şeyin gerçekten işe yarayıp yaramayacağına odaklanmışlardı. İdealler ve vizyon gibi şeylerle ilgilenmiyorlar pek. Devlet, merkeziyetçilik falan gibi konulardaki pozisyonlarını bu açıdan okumak lazım. Yine aynı sebeple, üretim araçlarının özel mülkiyetinin ortadan kaldırılmasında ısrar ediyorlar, çünkü bu olmadan sömürünün bitirilemeyeceğini söylüyorlar.

Sovyetler Birliği'ni (veya herhangi başka bir deneyimi) yeterince marksist olmamakla suçlamak bir mantık hatası. Marx'ın bizzat kendisinin sosyalizmin nasıl hayata geçirileceği hakkında pek fikri yoktu ve buna pek de kafa yormamıştı. Yabancılaşma, hak felsefesi, Paris komünü falan hakkındaki yazılardan, Marx'ın düşünce sürecinin derinliğini görmek mümkün; ama yine de ısrar edeceğim: Marx ve Engels yaşadıkları gerçek dünyadaki sorunları çözmeye çalışıyorlardı ve bence her türlü deney ve deneyimden mutlu olurlardı.

Ayrıca yine eminim ki sosyalizm girişimi ne olursa olsun Marx somurtup söylenirdi, Engels de heyecanlanır ve neşelenirdi.

- Engels Marx'tan çok daha erişilebilir ve çok daha keyifli. Engels'in yazıları daha eğlenceli ve daha basit. Tam da bu sebeple Engels'in sunumu Marx'ın eserlerine kıyasla daha az titiz olabiliyor. Marx bunların hepsini okumuştu, yani bir tutarsızlık olmaması lazım içerikte. Yine de mesela şunu düşün: bu ikisine Komünist Lig'in manifestosunu yazma ödevi verilmişti; Engels oturup bir şey yazdı (Komünizmin İlkeleri) ve Marx'a verdi; Marx buna baktı ve "Harika, bir gözden geçireyim çabucak." dedi ve tamamen bambaşka bir şey yazdı. Yani demem o ki ne olup bittiğini tam olarak anlamak istiyorsan Marx ve Engels arasında ayrım yapmakta fayda var.

- Marx pozitivist değildi (bugünün standartlarıyla da, kendi döneminin standartlarıyla da), kalkınmacı değildi (bugünün terminolojisi). Ne Marx ne de Engels avrupa-merkezciydi. Analizlerine belki "kapitalizm-merkezci" denebilir ama. Bundan kastım şu: kapitalizmin diğer tüm üretim biçimlerini yok edeceğini düşünüyorlar, bundan dolayı da kapitalizmin işleyişine odaklanıyorlar. Bu da bir yöntemsel tercih anlamına geliyor; kendilerinin kapitalizmin içinde konumlandırıp buradan kapitalizmin iç çelişkilerini inceliyorlar.

Kapitalist merkezin dışında kalan veya dışından gelen çelişkilerin farkındalar, Çin, Hindistan, "Doğu meselesi" yazılarından görebileceğin gibi. Ama bunları incelemiyorlar detaylı olarak.

- Marx'ın yazılarından tüm ekososyalist argümanın çıkarılabileceği muhtemelen abartılı bir iddia. Marx laf arasında çok ilginç tespitler yapıyor. Kapitalizmde yabancılaşmanın kapsamına dair çok derin bir içgörüsü var. Ama bir iki yerde geçen metabolik kırılma laflarından ekolojik çöküşü tüm boyutlarıyla çıkarımsamak bence pek mümkün değil. Yani, iklim kriziyle falan haşır neşirsen, Marx'ta senin öğrenme sürecine ciddi katkı koyacak bir şey bulabilirsin ve ayrıca bu sürecinle çelişecek hiçbir şey bulamayacaksın; ama iklim acil durumunun çözmek için sırf Marx'a bağlı kalırsan pek yol alamazsın sanıyorum.

- Tatmin olmuyorlar. Ne Marx, ne de Engels. Harika bir şey. Okuyorlar, not alıyorlar, birbirleriyle yorumlarını paylaşıyorlar - ve bunu hemen her konuyla ilgili yapıyorlar. Fizik, kimya, biyoloji, antropoloji, matematik, tarih alanlarında en güncel gelişmeleri takip ediyorlar Marx'ın matematik elyazmaları var. Engels'in atom teorisi hakkında da, bugün antropoloji diye adlandırdığımız alanda da kapsamlı yazıları var. Marx'ın bir de etnoloji notları var. Türlerin Kökeni'ni çıkar çıkmaz okumuş. Ve ayrıca, kendilerinin bu alanlarda bilim insanı olmadıklarını da biliyorlar. Yani, ne kadar ateşli eleştiriler yazmış olsalar da, bunları yine de (nihai söz olarak değil) bir araştırmayla ilgili kişisel yorum olarak okumakta fayda var.

E şimdi ne olacak?

Her şeyden önce, çok daha rahatım şimdi. Lenin'le, Mao'yla veya herhangi başka bir düşünürle aynı fikirde olabilirim yine. Lenin'le Lenin olarak aynı fikirde olduğumu (yani sırf marksist olduğu için değil) bilmek, karmaşık politik tartışmalarda dikkatimin dağılmasını önlüyor. Yani bu proje sayesinde kafam çok daha net.

Öte yandan, bu işe girişince birçok önemli eseri rafa kaldırdıydım. Yani mesela yıllardır neredeyse hiçbir ciddi sosyalistin kitabını okumadım. Şimdi bunlara yetişmeye geldi sıra.

*

Ha bir de asıl paylaşmak istediğim şu: Herhalde başka kimse için hiçbir manası yok, ama bu benim için ciddi bir başarı. Listemdeki son eser olan 1861-63 Ekonomik Elyazmalarını gördüğümde (iki bin sayfa), biraz cesaretimi kaybeder gibi oldumdu, ama sebat ettiğim için memnunum.

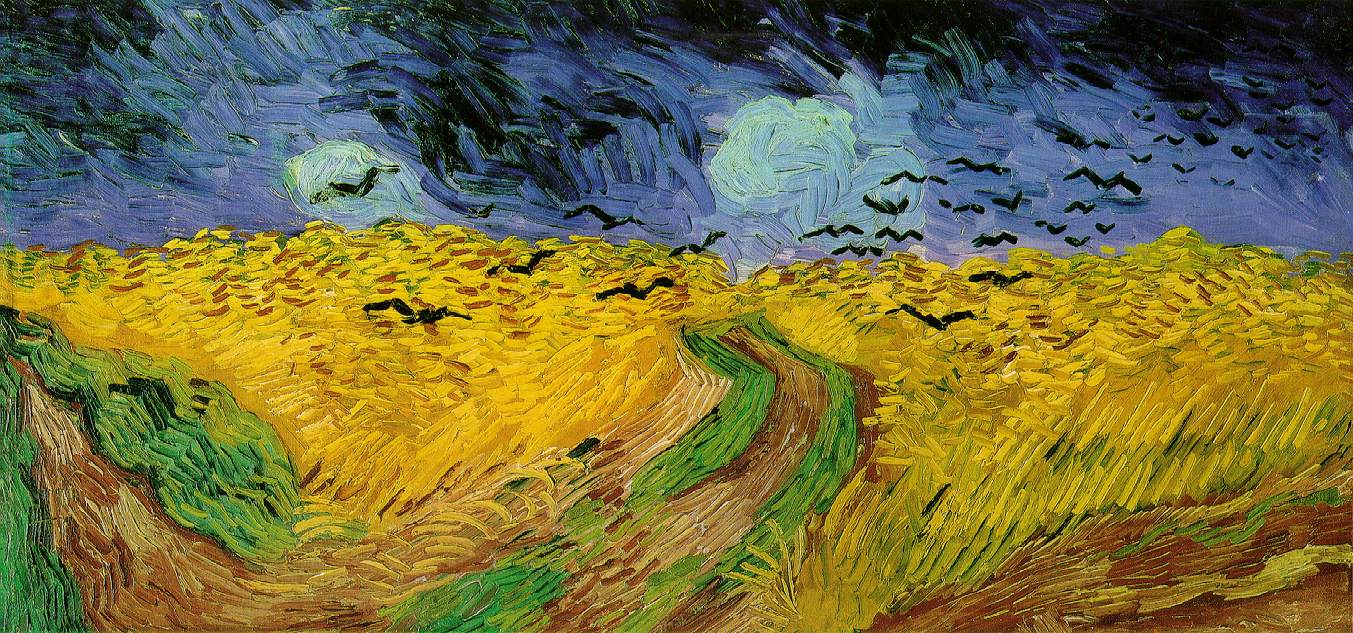

_-_Wheat_Field_with_Crows_(1890).jpg)