In June 2013, millions

all around Turkey marched against the AKP (Justice and Development

Party) government, confronting brutal police violence and risking

their lives. Western media suddenly changed its discourse; “mild

Islamism” disappeared to give way to “authoritarianism”. In

December 2013, a huge corruption scandal involving several ministers

including the prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan broke off. At the

same time, some dozen deputies of AKP who belong to the Gülen

movement (an international, Islamic-fundamentalist, mafia

organization that functions through deep state connections, until

recently in coalition with Erdoğan and unofficially taking part in

the government) resigned. It seemed like the ruling class coalition

was falling apart1,

as European and American representatives of imperialism started to

slowly withdraw their support from the government. Then came the

unbelievably corrupted local elections in March2,

the Mayday protests with the by-now-usual police violence, and

finally the outrageous mine explosion in Soma with at least 300

deaths.

During these political

thunderstorms and hurricanes, Erdoğan made a propaganda campaign

with posters of himself with the caption “Strong Will” in all

metros, billboards, bus stops and anywhere one could imagine. It was

as if he was personally fighting against all

the conspiracies against him. The peak of this was reached when he

literally punched a protester in Soma: As anywhere else in the world

in the good old days, you'd expect citizens to try to hit ministers

as a form of protest; in his case, he was protesting the people (o

povo / el pueblo) with full indignation – mind you, this was in

Soma after the mine explosion due to lack of safety measures and when

some 700 people were still missing.

Now, the question is:

How does he maintain his power (by now, AKP is identical to Erdoğan's

personality) in this turmoil? How is it that he, with his “strong

will”, never seems to doubt that he might be doing some mistakes?

This question needs a

two-sided answer: 1) Why does imperialism tolerate such a confused

situation in the only NATO country in Middle East? Why doesn't the US

“bring democracy” to Turkey? 2) If a huge portion of Turkish

society is outraged about the AKP government, how can Erdoğan remain

in power without sufficient consent from the population?

- Imperialism and Tayyip: The rather bearable lightness of lack of alternatives.

§1.

Erdoğan is arguably the most successful leader ever in Turkish

history. In his reign since 2002, he successfully mediated between

the interests of imperialism and his own political economic goals.

While passing all the imposed EU reforms on free trade, he managed to

consolidate all fractions of national bourgeoisie (including the

complete destruction of a liberal political party that had 9% of the

votes in 2002 elections). During the economic crisis, he slalomed

between NATO interests and his own medium-scale imperialist plans in

Middle East, and centralized all state apparatus in his personality

in such a way that “order” could not be obtained if he were taken

out of the equation.

§2. Given this crucial

role, there is also a lesson learned by imperialism since Bush

regime: If you don't have your alternative to impose, “leaving

things messy” may be quite complicated. (see Iraq and Afghanistan)

Especially in the presence of popular dissent, the political

instability resulting from a government substitution by imperialism

may be messier than ever. (see Egypt and Libya) Thus, using more

civilized methods such as providing armaments to opposition forces

(Syria), financing existing bourgeois movements that can attract some

popular support (Venezuela), and supporting and training militia

against the government (Ukraine) seems to be the Democrat method of

imperialism.

Add to this the fact

that Turkey is a NATO country, with military bases near Syria and

Iran that require political stability in case of an international

political crisis in the Middle East.

§3. Given this brand

new, Nobel Peace Prize winner approach, all imperialist agencies (in

cooperation with the biggest industrialists in Turkey as well as the

Gülen movement) tried to come up with an alternative to Erdoğan.

However, as explained in §1, this turned out to be a difficult task.

§4. This lack of

alternatives was hardened by the strong anti-capitalist tendency of

the June uprising. It was nearly impossible to canalize the anger of

the protesters to an existing “milder” bourgeois alternative.

- The People and Erdoğan: This is what fascism looks like.

§1. In the first years

of his reign, Erdoğan played the game with the rules. He modified,

reinterpreted and manipulated already existing laws to suppress any

possible opposition from other bourgeois fractions. He monopolized

almost all media (some %85 is now parroting government propaganda),

assigned his adherents to university administrations, and reallocated

almost all high-ranking state officials. When this was done, he

introduced a constitutional reform as his “knock-out” punch to

the separation of powers: From that moment on, all juridical

positions would be assigned almost directly by the government.

§2. As was revealed

with the leaked phone call recordings, while seizing control of the

state apparatus he coherently chose a certain fraction of bourgeoisie

over the rest, several times against the interest of the big capital.

§3. Then, when the

June uprising came, Erdoğan was fully aware that he was fighting all

alone against the masses, that imperialist powers would need time to

introduce an alternative, and that if he silents the protests as fast

as possible he could re-consolidate his power.

From the June uprising

onwards, politics has become a struggle for survival for

Erdoğan. Accordingly, he changed gears and declared war against

anyone who might have a reason to raise doubts about his leadership.

By now, police does not

hesitate to use real bullets when attacking a protest (a recent such

occasion caused the murder of two people in Istanbul) while Erdoğan

stated that regular and normal police practices were being

exaggerated by “some media”.

§4. This “change of

gears” had a two-fold effect: While trying to demonize and

criminalize the protesters (or, any kind of opposition for that

matter), Erdoğan also marginalized himself. He put himself versus

any protest, be a radical revolutionary action or a peaceful

democratic demand. He defined all opposition as an extremist, thereby

pushing himself to the other extreme.

All of a sudden, common

practices like male and female students sharing flats became immoral

acts, student protests became atheist and/or Jewish conspiracies

(which in AKP language means “the worst possible thing ever”),

Twitter and Youtube were categorized as means of sinful acts (and

therefore got banned), and the mine blast in Soma became a huge

international conspiracy against the government.

AKP got smaller and

smaller, while maintaining its power in the lack of imperialist or

popular alternatives.

§5. In addition,

Erdoğan realized that the June protests created huge opportunities

of dialogue in different sections of the opposition. An incredible

convergence of concerns occurred in the Gezi Park occupation: From

privatizations to domestic violence, from lack of LGBT rights to

ecological destruction, from labor rights violations to nationalism,

all protesters discovered that there was something common in their

sufferings: AKP policies and neoliberalism.

Feeling confident that

imperialism is doomed to his reign due to lack of alternatives,

Erdoğan wisely observed that there is nothing more dangerous for his

government (and in fact, for all his political career) than this kind

of convergence in the opposition. This had to be stopped. More

advanced water cannons had to be bought, and they were. All police

department had to be restructured to comply with his personal orders,

and it was. Any type of protest had to be oppressed immediately, and

they are.

- To conclude

On the one hand, the

convergence among June protesters seems to continue, as seen in the

funeral of Berkin Elvan, the mobilization against the Twitter ban,

and the protests following the Soma massacre.

On the other hand, this

convergence in mentalities has not yet found its concrete form

in active political convergence and ideological coherency.

When people come

together, they make an arithmetic sum, and it is another thing

to transform this into a vectorial sum that can exercise a

force to make a change. And this is indeed the – very

difficult – task in front of all political movements in Turkey.

***

[This essay was written for ATTAC Portugal. The Portuguese version was published here on June 9th, 2014.]

1“The

Political Crisis in Turkey” - Mehmet Baki Deniz, Sinan Eden.

https://network23.org/outforbeyond/2014/01/08/the-political-crisis-in-turkey-mehmet-baki-deniz-sinan-eden/

2 “Turquie:

Un pas de plus en dehors de la démocratie” - Sinan Eden (Propos

recueillis par M. Colloghan), Rouge & Vert, no 377, Avril 2014,

12-13. http://www.alternatifs.org/spip/IMG/pdf/rouge_vert377-2.pdf

The

English version of the same interview can be found at

http://pretendexistent.blogspot.pt/2014/05/turkey-one-more-step-away-from-democracy.html

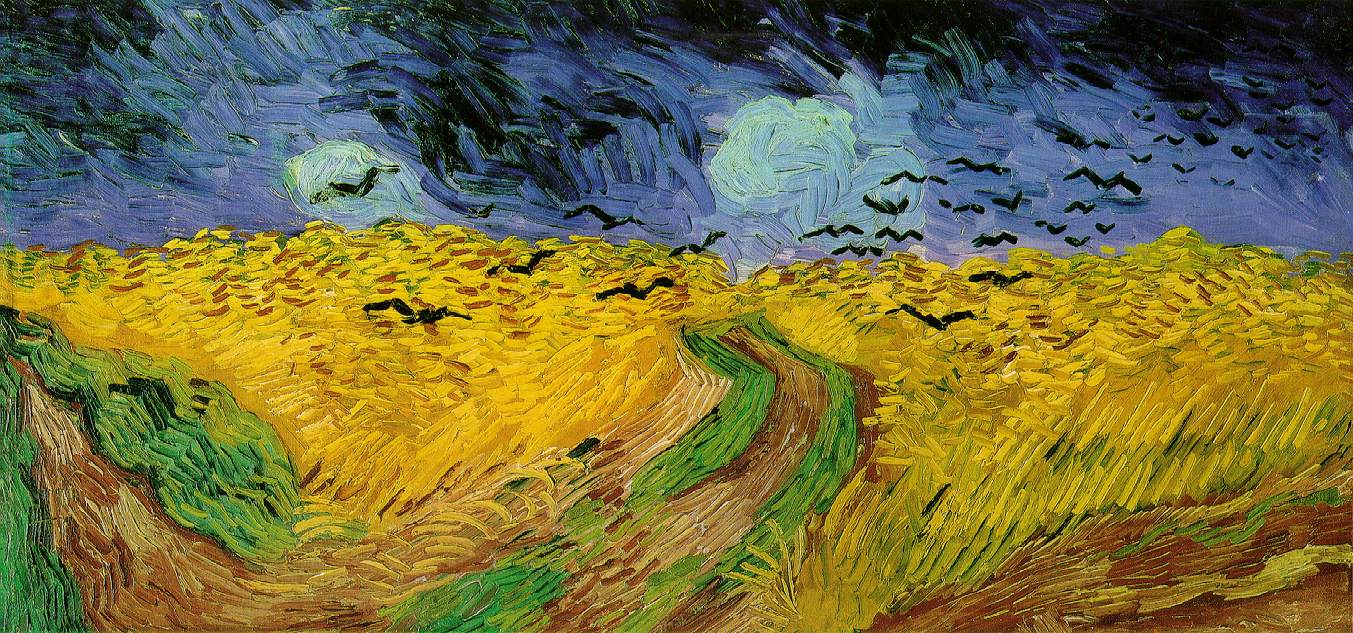

_-_Wheat_Field_with_Crows_(1890).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment