I am

a socialist, or a communist, or an anti-capitalist, whichever fits

your taste. I fight against the socio-economic system and the

injustices caused by it. I have been following the Unconditional

Basic Income (UBI) discussions for years now. I have four problems

with the proposal and/or how it is presented, which to my knowledge

are not answered yet.

1. Exchange value rather than use value

First

is a theoretical problem. It is about the monetarized formulations in

the campaign. We demand free healthcare and education for all. And

UBI campaign tries to enlarge this demand to other basic needs. But

instead of directly demanding housing, food and public transport, it

demands the supposed costs in the form of money.

The

problem with this approach is that it leaves the decision to the

market. We should never forget that 62 people own more wealth than

half of world population, and that the 1% is richer than the 99%

combined. The ruling class and their choices influence the prices

disproportionately more than us. Anyone who observed the

gentrification process in Bairro Alto or Alfama1

knows how that projects onto the right to housing, for instance.

In

fact, this monetary approach is perfectly compatible with the

capital's commodification motives. We should be demanding food,

housing and public transport for all, independent of their prices.

Introducing the price tag serves per se to amplify the

existing inequalities. Winning right to education is conquering a

fortress, winning UBI is shifting the battle itself into another

fight for what would be the fair basic income, to what products it

would be indexed, and how it would be updated.

While

UBI advocates like the simplicity of “one measure to solve it all”

motto, unfortunately this is not how reality operates. The simplicity

does help to spread the word and raise awareness, but it also hides

the fact that, in application, all that simplicity will be lost to

market obscurities and neoliberal technocracy.

A

campaign defensible by anti-capitalists should reject the liberal

discourse, instead of trying to frame its own agenda within it. We

want the basic needs to be outside of the universe of

commodities, and the UBI campaign is pushing to include them within

that universe.

2. A conflict-free proposal

My

second problem is an ideological one. It is another simplification

that undermines the UBI campaign, which is the proposal to include

“everyone, without discrimination” in the set of beneficiaries.

This kind of “equality in policy” is what bourgeois philosophy of

law has sold us since the beginning of modernity. These philosophers

tell us that we are all equal in front of law, for instance; but

anyone who ever challenged a company for its misconduct knows

otherwise. The ruling class not only has access to a herd of

sophisticated lawyers, they are also the ones who wrote the laws with

convenient loopholes and wording ambiguities. One could at most say

that the 99% is equal in front of law – well, unless you are a

person of colour, or of an ethnic minority, or of a gender minority,

or very poor, or homeless, or an immigrant, etc. etc. etc.

There

are no win-win policies in history. And the reason is simple: History

is the history of class struggles. Class struggle exists a priori,

the policy proposal comes on top that fragmentation.

I

understand that it is a populist approach to propose a simple policy

measure that would benefit everyone. But for this marketing strategy

to work, you should avoid telling what your actual proposal is.

Indeed, the UBI campaign seems to intentionally avoid from putting

content into what the campaign defends. This is also another reason

why political parties with government programs do not adopt the

campaign.2

A

campaign defensible by anti-capitalists should, in one way or

another, choose side in the existing class struggle(s).

3. Who will fight for it?

This

brings me to, my third point, a political problem with the campaign.

By avoiding social confrontation and promoting dialogue between

antagonistic political agendas, the UBI campaign fails to define

agency.

The

campaign discourse is that everyone can be persuaded to the campaign,

therefore everyone should be persuaded to the campaign, and so we

would win. The bad news is that “everyone”, “all of us”, “we”

have no social agency. A social movement can advance only if it

defines a class of people who would naturally benefit from this

struggle.

By

avoiding such political confrontation, the UBI campaign misses the

chance of mobilizing around this project. This is visible in its way

of organizing as discussion groups rather than a social movement.

This

attitude does allow for open debates where people with various

opinions exchange ideas, and I find this quite useful in a world of

social polarization. (Maybe the UBI advocates just wanted to bring

about dialogue and critical thinking to our societies; if so, they

have been doing a wonderful job.) However, as an anti-capitalist, my

priority is to fight the injustices of the current socio-economic

system, in campaigns that we should, can and might win.

4. The prey and the predator allied

Related

to this, there is a fourth point, a strategical one. The UBI

proposals have support from various ideological backgrounds, with a

strong presence of liberal economists and intellectuals. The UBI

advocates seem to welcome this diversity, but anti-capitalists should

beware. We shouldn't pretend class struggle does not exist. And the

UBI campaign runs the risk of putting the sheep and the wolf under

the same roof.

I

have respect to highly-educated bourgeois intellectuals and their

talent and tradition to draw lessons from history. I believe that

they see what I see in this campaign, and most probably more: an

opportunity for accumulation and centralization of the capital. And I

believe that this is why they are there. Of course, as any rational

wolf would do, they do not raise their voice against us but rather

use the pretext of win-win solutions as ground for persuasion. There

is no persuasion or collaboration of wolves and sheep.

The

UBI campaign proposes a form without specifying its content,

thereby allowing diverse opinions to encounter in a common platform.

For common people, this is quite useful exercise. But when

ideologists of the ruling class come in, it turns into a different

story, at least for anti-capitalist militants.

Building traps for one's self

In

conclusion, the strategy of the Universal Basic Income advocates to

present the campaign as conflict-free and widely inclusive brings

about a serious of weaknesses for the campaign. These weaknesses may,

in the worst case,open space to swaying towards neoliberal politics,

or, in the best case, produce a non-winnable campaign. I see very

little space for an anti-capitalist movement at any point in this

spectrum.

Most

UBI activists seem to share, implicitly, a set of values such as

justice and equity, with which I agree. They also seem to share a

common apologetic attitude towards the world they imagine, with that

I disagree. I believe it is crucial to openly declare what we want

rather than focusing on having faith on tricks in communication

strategies, because victory doesn't come without conviction and

honesty.

1Touristic

neighbourhood in downtown Lisbon, subjected to urban transformation

projects for years, resulting in raises in rents and living costs,

and gradual abandonment of the locals.

2In

Portugal, only PAN and Livre support the campaign openly. Not

accidentally, both parties have more of a philosophical wishful

thinking approach rather than strategies to seize the political

power. I am not necessarily saying this is a bad thing, perhaps

nowadays those approaches are more necessary than power-focused

programs. However, one cannot win a fight without a political

agenda.

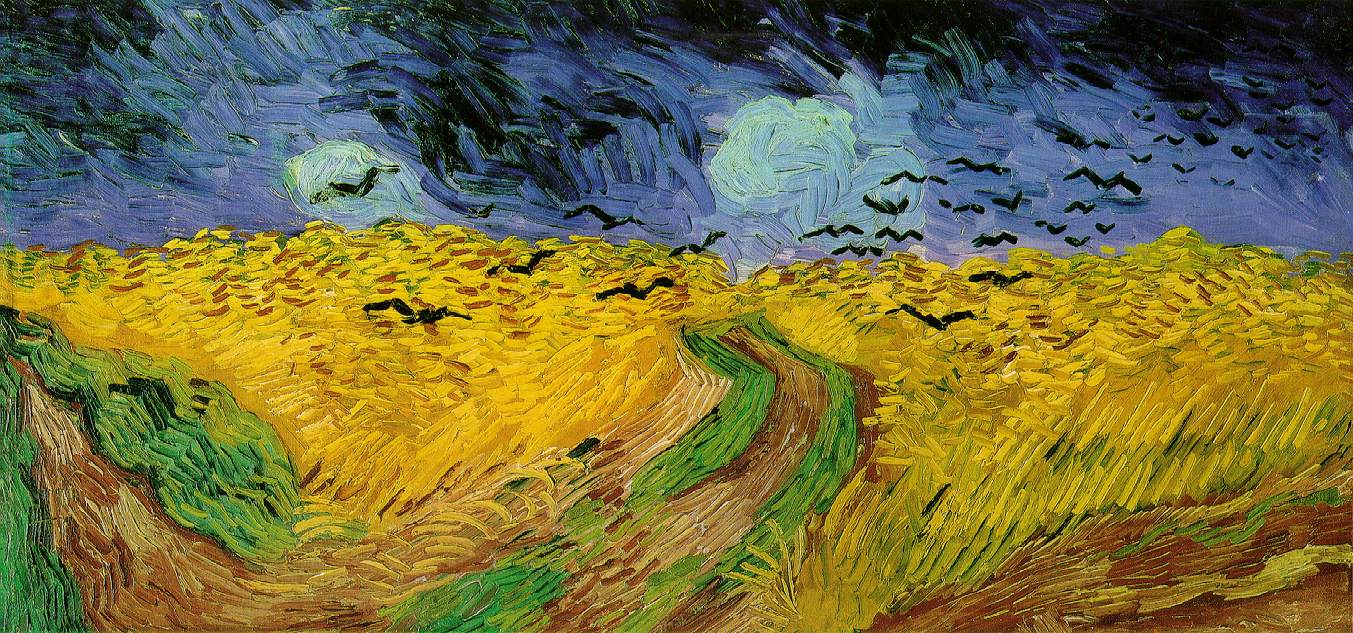

_-_Wheat_Field_with_Crows_(1890).jpg)