To my friend who works as a receptionist in a convent-come-hotel in the city center

to my friend engineer friend whose job is to receive and welcome tourists into Airbnb's

to my fifty-year-old friend who rides a tuk tuk

to my friend's date who repairs electric scooters

for young tourists' convenience in the hilly Lisbon

to my friend with a PhD who does morning bike tours

whenever his employee calls him

I say

their jobs are bullshit.

They should never have needed to get those jobs,

and their jobs shouldn't have existed.

Their jobs are not socially useful

and their jobs destroy the city,

the social fabric

and the local economy,

and promote a hypermobile

ultraconsumerist

planet-wretching

lifestyle for the few

and record breaking profits

for the few of the few.

My friends know and agree.

They saw the impacts.

First the poor had to leave the city

then the elderly

then middle-class families

- they themselves also either left already or about to leave.

They also know

that this is the exact same process

that created the "exotic holiday spots"

in Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas.

There were people there,

now there are hotels instead.

There were communities there,

now there are business opportunities instead.

I tell my friends

to march with me

for housing rights and an end to touristification

to campaign with me

to ban Airbnb's in our cities.

I recruit my friends

to fight with me

for the destruction of their jobs.

I admit;

that neither the housing march

nor the anti-Airbnb campaign

have any proposals to give my friends any income security

that the city's entire economy will have to be transformed.

I admit

that we'll have to talk

and figure things out together.

They march and campaign with me. I march and campaign with them.

*

Also

To my high-school friend who works as a flight attendant

to my childhood friend who works in logistics in an international airport

to my recent friend who works in a gas terminal

to my friend who emigrated during the crisis to work

in a transnational oil company

I say

their jobs are weapons of mass destruction.

Their jobs shouldn't have existed

and must cease to exist immediately.

The business they participate in

destroys livelihoods

disintegrates communities

burns entire ecosystems

floods entire cities

makes countries disappear

and collapses the physical-chemical conditions of a livable planet

while making record profits for the few.

My friends know about the climate emergency.

They see it now,

and they have a sense of what is to come.

I tell my friends

to march with me

to take direct action with me

with rage and solidarity

for climate justice.

I admit

that

while we do have a plan to secure them jobs and income

they will have to effectively fight against their current jobs

if we want to have a chance to win,

and that

the entire economy will have to be transformed.

I admit

that we'll have to talk

and figure things out together.

*

I must tell them the truth

because they are my friends

and because they are my class.

They will have to join me

because of their friends

and because of their class.

*

In short

A nuclear weapons factory worker

a soldier in a colonial army

a technician in an oil refinery

a real estate agent in the occupied West Bank

an administrator in a slave trading enterprise

a marketing consultant for SUVs

have a human right to not have these jobs

and a class obligation to fight against them.

Climate crisis means

exponential growth in human suffering

and run-away climate crisis means

unstoppable exponential growth in human suffering;

is what I must tell my friends

without hiding any bit of the meaning of it.

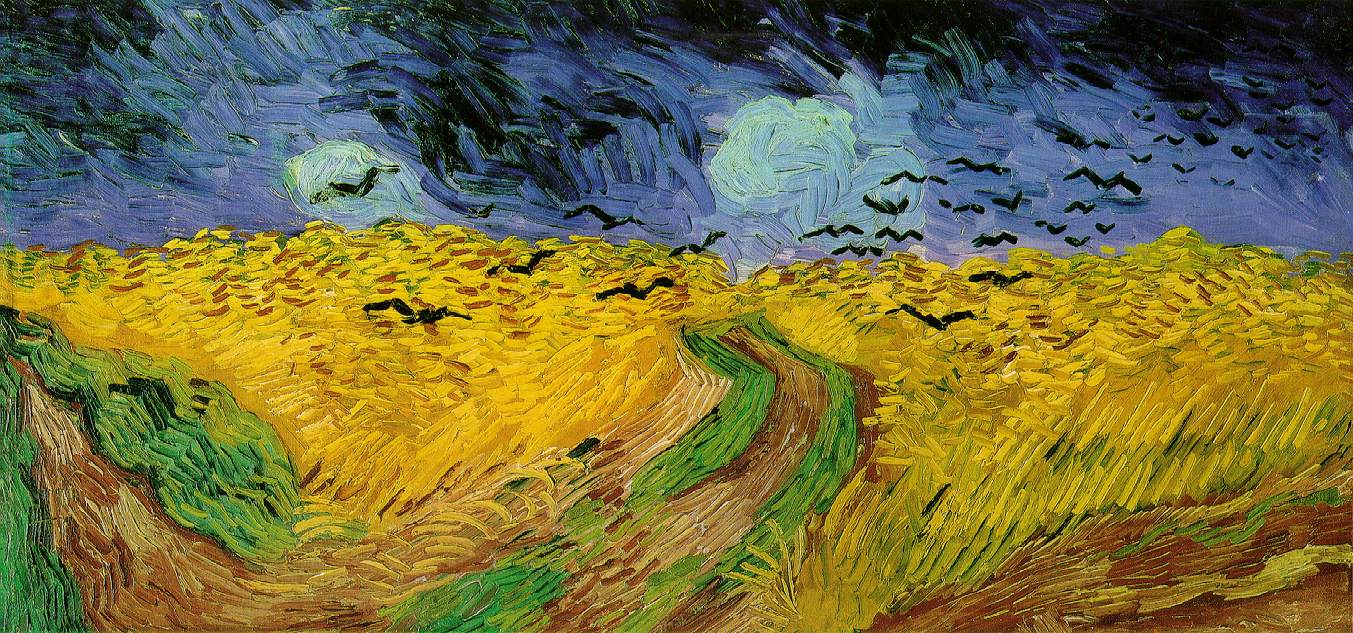

_-_Wheat_Field_with_Crows_(1890).jpg)