I finished a major personal project that I started some fifteen years ago.

I read Marx and Engels.

I mean, I read the Marx and Engels.

I read virtually everything that Marx and Engels wrote. And I finished this task just yesterday.

Why did I do that?

It was during my first years in university. I was searching for "what to do?". It wasn't really a strategy question but more like a mixture of "what am I supposed to do with my life?" and "how am I going to be useful to society?" and "how to save the world?". These are reasonable questions for a twenty-year-old, right?

Then I met many leftists groups.

So many of them.

They all had their own versions of answers to these questions. And they were in simultaneous processes of splits, infighting, divergence, convergence, merge, alliance and so on.

Some were anti-Marxists, some were Marxists, some were real Marxists, some were the most real original Marxists.

I got very confused.

There is no way they could all be right at the same time.

I got so frustrated. Centuries of debates, and it seemed like none of the main debates came to a more or less consensual conclusion.

So I decided that I wouldn't get carried away by the interpretations. Instead, I committed myself to reading the primary sources, establish my version of what Marx and Engels said, and only then get carried away by the interpretations.

This was in 2011. I stopped reading Marxists almost entirely, and started reading Marx.

What did I do, exactly?

I read the works of Marx and Engels, in chronological order.

When I say works of Marx and Engels, I mean

- everything that came out as a book in their time (the three Capitals, the early polemics like Holy Family, the later polemics like the Gotha program stuff, books on daily politics like Brumaire, the more textbook-like things including Anti-Dühring or the Feuerbach stuff of Engels, etc.)

- all the correspondence around the Communist League and the First International,

- most of the manuscripts (1844 philosophical and economic stuff, Grundrisse, 1861-63 economic manuscripts),

- most of newspaper articles,

- half of all the letters.

Basically, if you go over the list of all their works, I read everything that is bold in here, except the letters (which were impossible to find in compiled form, unless you pay a fortune to MECW volumes).

What did I learn?

I learned that most Marxists and almost all anti-Marxists have no idea what Marx was saying. They generally start with their opinion, then try to find that opinion in Marx's writings.

Most of the time, when someone says "Marx said this." or "Marx was like such and such.", they are quote-mining at best or are referring to an interpretation of an interpretation of an interpretation.

More concretely, I can share with you a few observations:

- There is a lot of context that we are missing. Half of their work is about arguing against other people to make a specific criticism. Most of the quotes that people pick were not written as general statements, but rather as specific comments to specific nonsense of the time. So they are not "quotable". These people were writing thousands of pages of polemics against each other; and most of the times it's not possible to reduce their meaning into a tweet just because a sentence sounds cool.

- Also in terms of context, we are missing terminology: I needed a lot of unlearning because I was reading the texts as if they were written in today's language. But words like "organic" (organ-like), "objective" (related to an object) and "contradiction" have different meanings today than they did for Marx and Engels.

Since more than half of their work is about criticizing political economy, they also use a lot of that framework. They were part of an ongoing debate, so they use contemporary terminology. Stuff like "most advanced mode of production" have a sense of "progress" that is carefully defined in terms of "productivity of labour", and here "productivity" is defined as "produces surplus value for someone else". It really helps to know what the words stand for, if you want to understand what the text tries to transmit.

- One important thing I learned is the method. The content changes because the context they address is changing. If you pick quotes from the books on German peasant struggles and on the critique to the Erfurt program, you will find contradictory sentences. That's because they are talking about different things. The constant here is the historical materialist method. They apply class analysis and dialectics to existing situations and reach concrete conclusions.

- Both Marx and Engels are very much focused on what would actually work. They do very little debate on ideals and their vision. Their takes on state and centralized power structures should be read with this lens. Equally, their insistence on abolishing private property of means of production is because that's the only way exploitation could be stopped.

It is a straw man fallacy to criticize the Soviet Union (or any other experience) for not being Marxist enough. Marx himself didn't know how to execute socialism, nor was he very worried about figuring that out. The writings around alienation, philosophy of right and the Paris commune point to the depth of his thought process; but again, Marx and Engels were trying to solve real-life problems so I think they would be happy with all kinds of experimentation.

I am also sure that Marx would be grumpy about any attempt, and Engels would cheer up with almost any attempt.

- Engels is much more accessible and a lot friendlier than Marx. Engels' texts are fun and simple. For the same reason, Engels' presentations are less rigorous than Marx's works. Marx read all of them so there is nothing inconsistent in them. However, keep in mind that they were given the task of writing the manifesto for the Communist League. Engels wrote something (The Principles of Communism), gave it to Marx; Marx looked at it and said "Wonderful, let me go over it." and then wrote something completely different. So it's useful to distinguish Marx and Engels if you want to understand what's actually going on.

- Marx is not a positivist (neither in today's standards nor for his time) and not a developmentalist (in today's terminology). They are not eurocentric. Their analysis is maybe "capitalism-centric". By this, I mean this: they think capitalism will destroy all other modes of production so they focus on its dynamics. This means that they make a methodological choice of situating themselves within capitalism and analyzing internal contradictions.

They are aware of contradictions external to the capitalist core, as their writings on China, India, the "Eastern" question etc. show. But they don't investigate that stuff.

- It is probably an exaggeration to argue that the entire ecosocialist argument is intrinsic to Marx's writing. I mean, he makes some really intriguing remarks in passing. He seems to have a very profound insight about the extent of alienation in capitalism. It was not possible for me to deduce the full scope of the ecological collapse just from some metabolic rift stuff. So, if you are into climate crisis, there is a lot of inspiring comments in Marx to feed your thought process and you will not find contradictions; but also, you cannot rely entirely on Marx to be able to solve the climate emergency.

- They are unsatisfied. Both Marx and Engels. And I find this incredible. They are reading, taking notes, commenting to each other, on virtually every topic. They know the most up-to-date developments in physics, in chemistry, in biology, in anthropology, in mathematics, in history. Marx has mathematical manuscripts. Engels wrote extensively on atomic theory as well as what we could today call anthropology. Marx also has etnography notebooks. He read The Origin of the Species when it came out. They are also aware that they are not the scientists of all these disciplines. So even though they express very strong opinions about them, you should still read them as comment/review of a research rather than the final take on a specific topic.

What now?

First of all, I am much more comfortable. I can still agree with Lenin or Mao or whoever else, but the knowledge that I am agreeing with Lenin as Lenin (and not with Lenin because he is a Marxist) helps me navigate complex political discussions without getting confused. So basically, this project provided a lot of clarity for me.

On the other hand, I postponed many of the essential readings. So I actually never read an entire book by any serious socialist, for a long time. Now I will have to catch up with that.

*

So just to share with you: It surely doesn't mean anything to anyone else, but this was a massive accomplishment for me. When I saw the last item 1861-63 Economic Manuscripts (a bit more than 2000 pages), I was a bit discouraged. But persistence paid off.

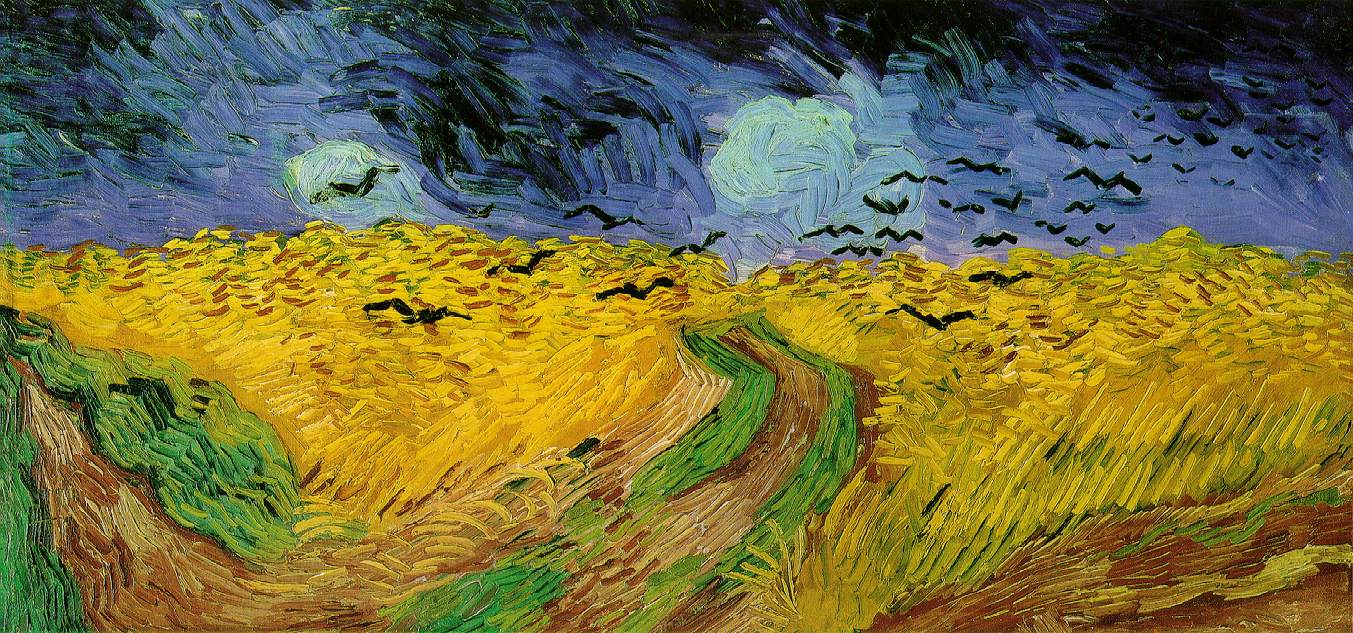

_-_Wheat_Field_with_Crows_(1890).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment